Readings:

Reading I: Isaiah 11:1-10

Psalm 72:1-2, 7-8, 12-13, 17

Reading II: Romans 15:4-9

Gospel: Matthew 3:1-12

In May 1945, the Art Institute of Chicago hosted a touring exhibition of contemporary American paintings owned by the Encyclopedia Britannica. Included in the collection was the first of a four-painting reflection on Isaiah 11: 6-9 by the African-American self-taught artist Horace Pippin. Pippin’s foray into art as a profession was accelerated by a disability resulting from injuries to his right arm sustained in World War I. He had fought in a racially segregated USA military as an enlisted soldier in the heralded Fifteenth Regiment of the New York National Guard, an African-American unit nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters.

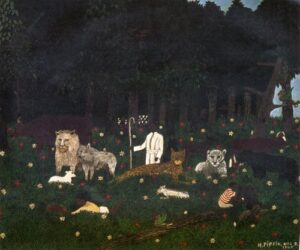

From 1944-1945 Pippin completed three paintings in his series of Holy Mountain images inspired by his interpretation of verses we find in the first reading for this Second Sunday of Advent. In the foreground of all versions of the paintings, Pippin features a variety of wild and so-called domesticated animals. Like the creatures named in Isaiah, they reflect a spectrum of prey and their predators resting peacefully in proximity to each other and to two children. At the center of this idyllic paradise where “the wolf shall be a guest of the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the young goat” (Is 11:6) is a pastoral figure with shepherd’s staff that some believe, in the first and third iterations, is a self-portrait of the artist. In his own written words, that appear with Holy Mountain I in the exhibition, Pippin explained the motivation that drove him to contemplate Isaiah, “The world is in a Bad way at this time. I mean war. And men have never loved one or another, There is trouble every place you Go today. Then one thinks of peace” (1945, 44).

What further distinguishes Pippin’s painting is his allusion, in the background, to the violence that shaped his perspective and ruptured the peace of his own times. “Now my picture would not be complete of today if the little ghost-like memory did not appear in the left of the picture. As the men are dying, today the little crosses tell us of them in the first world war and what is doing in the south today—all of that we are going through now” (1945, 44).

Pippin’s cryptic reference to race-based violence becomes more obvious in the next two paintings with his depiction of a victim of a lynching concealed among the trees. The violence of two world wars finds expression in the backgrounds across the series with silhouettes of soldiers, and in varying ways with the weapons of war–planes, bombs, tanks. In Holy Mountain III in particular, a cemetery of white crosses ties the consequences of violence together and takes on another level of meaning because the service of Black military in both wars did not eliminate the deadly cost of racism on Black bodies and the soul of the nation.

Yet still Pippin dreamt of peace.

The jarring juxtaposition of harmony in the foreground with destruction in the background is further complicated by memories and signs indicating that the artist’s hope for peace was not naïve and his lived experience bore witness to this reality. The brutality and trauma of a global conflict that decimated a generation of young men–physically, emotionally and socially–peeks through the tranquil field dotted with red poppies in Holy Mountain III. The red poppy as a symbol of remembrance remains inextricably linked to the losses of the war that threatened the artist’s own life, health and ability to secure economic stability as a Black and disabled veteran. Each painting references, with Pippin’s signature, a notable date in the second world war: Holy Mountain I, June 6, 1944 (D-Day); Holy Mountain II, December 7, 1941 (attack on Pearl Harbor); Holy Mountain III, August 9, 1945 (atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki).

In the Holy Mountain series, we encounter Pippin as an invested interpreter who, for almost two years, sits and interacts with a singular biblical text from within his own contemporary context of global and national upheaval, and then preaches an unfolding word through his art. The tension palpable in these paintings signals the fragility of peace and the not-yetness of justice. The possibility that the shepherd figure is indeed the artist himself may indicate a realization that vigilance and action are called for by those committed to the dream of God’s holy mountain.

Horace Pippin died in July 1946 at age 58 from a stroke, leaving behind a minimal sketch of Holy Mountain IV. We will never know how he envisioned a tenuous postwar peace with an ongoing struggle for racial justice because all we have in that last image is a mountain, a bare tree and three creatures considered predators: a lion, a leopard, a wolf.

This Advent how do we situate ourselves in-between a dream for peace and the violence of our day? Do candles, teddy bears, and countless tweets of “thoughts and prayers” dot the fields in our foreground while in the shadows lurk the unregulated weapons of our day? What do we do as the tranquility of our dreams for God’s holy mountain continues to be shattered by hate speech and cruelty, especially toward those who are made most vulnerable? What do we need to do so that we are no longer predator and prey to each other?

Sources:

Horace Pippin, “Horace

Pippin Explains His Holy Mountain,” Art Digest 19, no. 13 (April 1, 1945):44, https://archive.org/details/sim_arts-magazine_1945-04-01_19_13/page/44/mode/2up.

Links to images of the Holy Mountain series by Horace Pippin: